I have had several careers. I started in finance trading foreign exchange options for a bank right after the British Pound fell out of the Exchange Rate Mechanism. This was a great opportunity to learn. It was the blue collar of trading. It was an extension of the money-markets. These weren’t the gods of the bond market, nor were they the cowboy risk-takers of equities.

Our job was to make two-sided markets to customers looking to manage their foreign exchange risk. Imagine an American company that sold widgets in Britain. They would want to make sure that they could protect the economic value they created in the sale from movement in the foreign exchange rate. They weren’t in the foreign exchange business; they were in the widget game.

To be able to provide liquidity to our customers, we needed to have the ability to move product in the market ourselves. So we had to provide liquidity to other banks to create a reserve of goodwill that would enable us to manage our own risk by laying it off when necessary.

There is a difference between trading and investing.

In foreign exchange, I was a trader. I was a principal most of the time. I would make them a price. If they sold something to me, I would hold it in my inventory. If they bought something else from me, I would create it synthetically, holding the opposite position in my inventory. When I didn’t like the way the book looked, or when I was bumping up against the limits of different dimensions of risk I was permitted to hold, I would have to go into the interbank market to reduce my exposure.

Sometimes, I would act as an agent. If a customer wanted an obscure currency trade, say purchasing Korean Won, in which I had no inventory nor any desire for it, I would call up a Korean bank and do a “back-to-back” trade, acting as an agent, assuming only the credit risk of each counterparty.

Acting as either principal or agent, my job was to retain as much of the bid-offer spread I charged as possible. When I dealt in the interbank market, I would either cross some other institution’s spread and pay them the bid-offer differential for taking the risk off my hands, or I might sit on the bid or the offer in one of the interdealer brokers. Losing money on the inventory ate into my retained spread. I was an insurer seeking to keep as much of the premium as I could after paying out claims.

My risk was short-term. I would hold a view in the book, tilted long volatility or directionally long Canadian dollars, for example, but this was principally in anticipation of the demand customers would have as the markets moved in those directions. I could maximize the amount of bid-offer spread I kept and reduce the need to chase prices.

This required tremendous discipline. Banks had risk management departments, the sole purpose of which was to enforce this. This manifested in the form of limits, including guardrails on how much business you could do with an individual counterparty, or different dimensions of risk you could “take home” at night. Too tight and the bank left money on the table. Too loose and the bank was vulnerable to the trader’s skill, luck, and self-control.

Now, some traders would anticipate the future incorrectly. They would position for interest rates in country A to go down with respect to country B, changing the forward spread. But it would go against them.

We had one trader named “Bobby” who did this all the time. He was a forward trader who would come to the spot desk to put on trades. It was always a “hedge” or so he claimed. But the hedge would go against him. After a few weeks in the book, it became an “investment” that ceased to be a topic of conversation.

We loved him. He was a good guy. We knew what he was doing. We pestered him about it. We were young and stupid.

The problem with this was the opportunity cost. These positions used up some of his limits. They required some of his allocated capital. Consequently, these “investments” had opportunity costs because had he the discipline to cut them early, potentially realizing small losses, he could have used this freed up capacity to make money on other trades. The profits he had foregone by lacking the will to cut losers early were the opportunity cost of his indiscipline.

So what does this have to do with procurement?

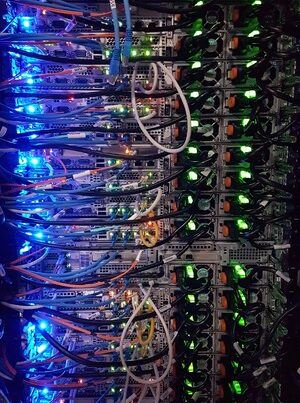

Companies buy lots of things. They can buy consumables, such as test tubes or reagents. They can buy large systems such as cloud computing services. In either case, the decisions they make have long-lived consequences in practice. They are unlikely to change cloud-computing service providers anytime soon. Even with the frequently purchased commodities, they will buy the same things from the same people, the same way, for years to come.

Procurement is investment. It’s not just about transactions costs (i.e., what you spend to execute the process of identifying solutions and selecting one). It’s not just about the deal costs (i.e., the price of the solution you select, such as cloud services). It’s about making sure that you pick the right solution for the problem you want to solve with this acquisition. It requires you to identify and engage as many solution providers as possible so that you can make an informed decision. Because your company will live with it (and live with the supplier) for years. Procurement is investment because it should be focused on reducing opportunity costs that can dwarf the transactions costs or any marginal savings on deal costs.

There is no item on the income statement called opportunity costs. It’s not in the statement of cash flows or the balance sheet either, at least explicitly. But it’s there, nonetheless. It hides in the form of higher cost of goods sold or higher operating expenses because the better solution that the buyer could have purchased might have had a lower total cost of ownership. It’s there potentially in the form of lower revenue because the supplier who offered the marginally lower price isn’t as reliable as the one with the slightly higher price. Or the supplier with the slightly lower price constituted a lower quality input that led to lower customer satisfaction for the buyer’s ultimate offering.

How do good buyers minimize opportunity costs? They generate as much competition on price and solution as possible by making it easy and desirable for vendors to engage with them. They research markets completely and principally, getting market intelligence from other buyers as to what these solutions do in reality (and not in marketing) and what they should cost. They collaborate with suppliers to ensure that both sides know what the other side does and needs out of a transaction. They develop relationships.

This is what EdgeworthBox was built to do. We offer a set of tools, structured data, community, and market intelligence. Buyers and suppliers get free baseline access with an unlimited number of seats for free. When they want to execute a transaction, they pay a fee. We help them generate competition on price and solution so they can buy the right solution, from the right supplier, at the right price. We call it elastic procurement™. What’s more, we uniquely have collaboration features so that they can cooperate with other buyers, as well as develop relationships with their suppliers. Give us a shout.